What Is a Sovereign Cloud? Why Is It Important?

Alan Zeichick | Senior Writer | September 5, 2025

Start with a proposition: Some or all of your organization’s data must stay within a certain national or regional geographic boundary, whether a state or country or a broader region, such as the European Union. Reasons for this requirement vary. Perhaps there are governmental rules covering your industry or you manage specific types of regulated data, such as personally identifiable information (PII). There may be business-specific or competitive concerns. Whatever the underlying reason, the requirement is called digital sovereignty or data sovereignty.

One approach to satisfying digital sovereignty requirements is to store everything in a data center within the country or region. Another is to use the cloud—specifically, a sovereign cloud that’s designed to offer all the advantages of cloud computing while helping you meet your individual sovereignty requirements.

What Is a Sovereign Cloud?

A sovereign cloud is a cloud environment that helps an organization meet its digital sovereignty requirements while delivering the benefits of the cloud model. A sovereign cloud may be housed at a facility owned by a cloud computing provider and accessed by an organization’s user and non-cloud IT systems over the internet or via dedicated communications links that aren’t connected to the internet. A sovereign cloud may also be configured as a separate “cloudlike” installation within a large organization’s own data center; the installation acts like a cloud environment and is maintained by the cloud service provider, but it’s physically isolated from the outside world. Because of the way cloud computing works, there’s a shared responsibility model between the provider and the customer. Security and privacy must be jointly managed, so it’s critical to select a provider that can help you meet your sovereignty needs.

There are four tenets of digital sovereignty: data residency, data privacy, security and resiliency, and legal controls. They encompass common questions such as: Where is my data? Who can access it? How is my data kept safe? What legal protections do I have? Under most sovereignty frameworks, organizations look to protect personal information about individuals. However, sometimes the scope is broader, encompassing intellectual property, software, business methods, financial data, information about IT infrastructure, and even metadata that describes how big a data set is and how quickly it’s growing.

Note that digital sovereignty isn’t a binary concept. It’s more like a spectrum and evolves over time. Organizations need to constantly adapt to changes in laws and the digital world. Let’s explore the requirements for digital sovereignty, discuss how a sovereign cloud can help an organization stay compliant, and address key tenets and questions.

6 Sovereign Cloud Capabilities

In many cases, sovereignty compliance requirements go beyond the storage of databases. All the computers that process regulated data may be required to be within a geography, along with all the networks, data flows, backups, and disaster recovery systems. Sometimes, even the people who have access to regulated systems must be citizens of that jurisdiction or have specific security clearances. That means a sovereign cloud will have some level of one or more of the following six capabilities; the specifics generally depend on regional and other requirements.

1. Access restrictions that limit use of the sovereign cloud to users, software, systems, and services belonging to a company and its partners, customers, and suppliers; geographic regions; or even individuals within an organization who have specific citizenship or security clearances

2. Organizational control over where the sovereign cloud is located, such as in a certain country or region, or whether the cloud is in a service provider’s data center or the customer’s data center, often referred to as data residency

3. Compliance with governmental, regulatory, or industry requirements, including technical specifications, as well as specific legal, contractual, and business practices to meet relevant laws and regulations

4. Operational support from the cloud service provider that meets high customer expectations and legal requirements for the security clearances, citizenship, and residency of its employees

5. Dedicated network capacity, which may mean anything from secure VPNs over the public internet to air-gapped regions that are completely isolated from the internet and the cloud provider’s other customers

6. Sophisticated encryption, which could involve the cloud service provider maintaining encryption keys or the customer bringing their own keys that the cloud service provider can never see or access

Key Takeaways

- Implementing digital sovereignty via a sovereign cloud helps with data compliance, business continuity, supply chain efficiency, and geopolitical resilience.

- The challenges of cloud sovereignty include finding a service provider that knows all the rules, can help determine the necessary levels of protection, and holds the relevant certifications.

- Sovereign clouds are generally connected to the internet and accessed by secure, encrypted links and protocols. In some cases, an air-gapped cloud may be required.

- Data sovereignty requires that data be encrypted with an approved set of protocols, whether it’s stored in a database or file system or being transmitted over a network.

- Assume that digital sovereignty laws and regulations will increase in number and complexity and that there will be significant financial and criminal penalties for failing compliance audits or breaches that expose regulated data.

Sovereign Cloud Explained

To understand what a sovereign cloud can do, imagine you run a company that does business in the European Union (EU). The EU is an ideal test case because not only does it have overall requirements, but so too does each of its member nations. Therefore, every organization charged with maintaining digital sovereignty within the EU must meet both EU and national requirements.

Within the EU, cloud sovereignty laws are guided by an interlocked web of regulators, and regulations are constantly changing—in general, becoming stricter. Much of that regulatory evolution is driven by national parliaments and the European Parliament in Brussels in response to both citizens’ demands and constant political pressure for protection against foreign business interests, law enforcement, and courts. That’s where laws such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) come in.

Imagine that an organization has subsidiaries with offices, employees, and customers in both Germany and France. There may be some data that can be shared between the two countries while complying with EU requirements, while other data may be restricted by German or French laws and must remain only within the specific country. Both the customer organization and the cloud service provider share responsibility for ensuring the sovereign cloud can meet all those requirements and—just as critical—that it’s configured to do so in ways that are demonstrable to all parties.

A proper EU-compliant sovereign cloud will include EU-wide sovereignty to provide customers with control over data and data flows in compliance with EU regulations; bring in non-EU access protections to detect, challenge, and block access from outside the EU; and, as appropriate, handle stakeholder notifications and allowable waivers.

The CLOUD Act

The Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act, or the CLOUD Act, is a US federal law enacted in 2018 as an amendment to the Stored Communications Act (SCA) of 1986. The CLOUD Act primarily addresses the access and disclosure of data stored by service providers, particularly when that data is located outside the United States. It provides a framework for US law enforcement agencies to compel US-based service providers to disclose requested electronic data, including emails, documents, and other communications, regardless of where the data is stored globally. This provision simplifies the process of accessing data stored in foreign countries in cases where the provider is subject to US jurisdiction.

Benefits of Cloud Sovereignty

Establishing a sovereign cloud can be a complex undertaking, even with a capable provider. However, it pays off in a variety of ways. First and foremost: compliance. Cloud sovereignty broadly addresses geographic, political, and industry regulations, data portability, and compliant data transfers within and between regulatory domains.

In addition, a sovereign cloud delivers the following benefits:

- Technical solutions and expertise companies may not have in-house: Digital sovereignty can pose difficult changes on the technical front, especially if an organization wishes to maintain interoperability and portability. A well-constructed sovereign cloud offers both regulatory compliance and open standards.

- Operational best practices: A sovereign cloud provider will have in place strong operational controls, such as authorized key access for customers or the ability to bring your own keys, as well as administration, logging, and technical support. This is critical for a range of organizations, such as the intelligence community.

- Business and continuity assurance: A sovereign cloud installed and maintained by a top-tier provider offers all the scalability, business continuity and disaster recovery, redundancy, portability, and performance of a first-class cloud—with digital sovereignty as well.

- Supply chain sufficiency: A cloud service provider that offers a sovereign cloud can often go beyond a single customer organization’s ability to source servers, networks, chips, cabling, and the energy, facilities, staffing, and training required for round-the-clock availability.

- Geopolitical resilience: A sovereign cloud service provider with global reach can help organizations weather challenges posed by military conflicts, economic hardships, climate change, and other large-scale disasters, assisting with sustainability.

5 Challenges of Cloud Sovereignty

Sovereign cloud service providers have an interest in helping customers meet their regulatory, legal, and technical requirements. Still, despite the benefits, establishing cloud sovereignty requires an organization’s IT team to overcome some obstacles, including the following:

1. Finding a service provider that knows the rules

Digital sovereignty laws and regulations are complex and becoming more so constantly. Whether organizations use a sovereign cloud or a traditional data center, the regulatory landscape makes it difficult to know what's compliant and what isn’t. A full-service sovereign cloud provider will have both expertise and processes in place to keep its offerings up to date as regulations change.

2. Determining the necessary levels of protection

Does an organization merely need to ensure that personally identifiable information (PII) is properly encrypted and stored within national boundaries, or does regulatory compliance extend to the servers housing a document repository, the control systems, and the citizenship and security clearances of all staff with physical access to the hardware? You can’t comply until you know what’s required.

3. Designing a disaster recovery architecture

Cloud sovereignty applies to not only the primary data center but also all backup recovery sites and facilities, which means the cloud service provider must have sufficient resources to offer such facilities within the defined jurisdiction.

4. Robustness and completeness of the sovereign cloud

Some service providers have built specialized sovereign cloud offerings. As a result, the applications, features, and services they offer in their public clouds may not be available, or fully available, in their sovereign clouds.

5. Acquiring a full set of certifications and legal entities

Some regulatory regimes require the sovereign cloud to be owned and operated by a service provider headquartered and owned within the specific geographic region. Ensure that a global cloud service provider has the right partnerships, licenses, and legal frameworks in place to meet those requirements.

5 Key Features of Sovereign Clouds

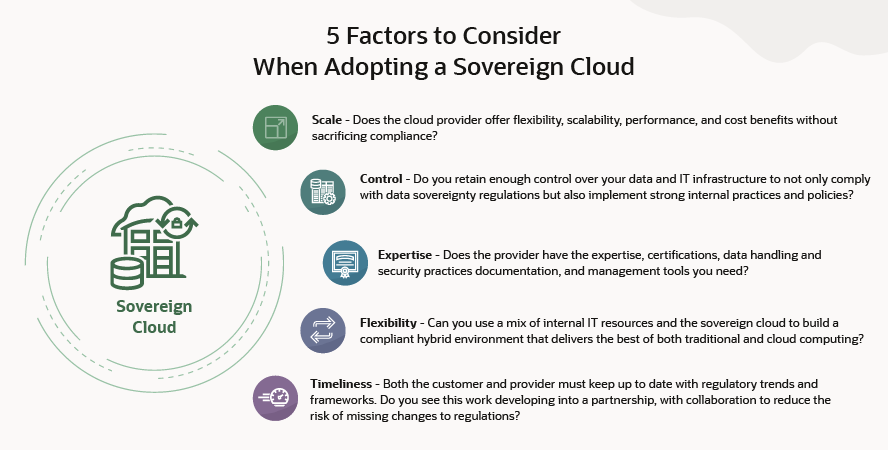

Companies looking to establish sovereign clouds will need to consider their requirements for these five key features, in addition to any industry-specific or competitive factors at play.

1. Location

Carefully select the location of your sovereign cloud data center and backup locations based on both compliance regulations and business considerations. Data points to collect include the location(s) of the provider's cloud data centers, the location(s) of other data centers owned by partners, and whether a dedicated sovereign cloud inside the customer’s own facility is feasible.

2. Access control

An organization should always be able to choose which companies, partners, customers, and software and services can access its cloud environment. In some cases, such as when national security is at stake, the customer may choose a fully dedicated facility.

3. Operations and support

An organization should control which administrative and technical staff, from both the cloud provider and its partners, may have access to their systems, as well as to metadata about those systems, such as performance and utilization metrics.

4. Regulatory compliance

Sovereign cloud deployments must be flexible when enabling compliance with regulations and security standards to reflect the possibility of overlapping jurisdictions, each with its own requirements. In some cases, a customer may have unique needs for specific regulatory controls and accreditations.

5. Internet connection or air gap

For many or most customers, an encrypted connection to the public internet may be the best, most affordable compliant network link. However, some customers or applications may require air-gapped regions totally isolated from the internet or other networks.

Data Sovereignty and Encryption

You can’t have data sovereignty without encryption, and that goes for data stored in databases, the APIs and other services that provide access to those databases and applications, and user interfaces. Encryption is a complex subject due to the number and versions of commonly used algorithms, the size of the keys, and regulations regarding storage of and access to the encryption keys. This is true whether data sovereignty is enabled within a traditional data center or in a sovereign cloud—though in the case of the cloud, questions about the storage of and access to encryption keys must be resolved in a way that is both compliant and meets business needs.

When a cloud service provider manages the keys, the master encryption key is generated by the sovereign cloud software; when the customer manages the keys, the master encryption key is stored within a secure key vault the provider can’t access. The hardware security module (HSM) comprising those key vaults should be both tamper resistant and tamper evident and able to react if attacked.

Data stored in a database or in a document—sometimes called “data at rest”—should be encrypted by default. This includes data in traditional relational databases, Docker/Kubernetes containers, object databases, file systems, block databases, and even boot records.

Information that is being transmitted over a network—sometimes called “data in transit”—should use up-to-date protocols compliant with standards such as Transport Layer Security (TLS) 1.2 or later and X.509 digital certificates, at a minimum. Local regulations may require even stricter encryption, such as MACsec (IEEE 802.1AE) for Ethernet networks. Such encryption should be enabled by default and never allow data transmission in plain text.

The Future of Sovereignty

Data sovereignty may have exploded into public view with the passage of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in 2016, but that was only the beginning. Each year, countries around the world, as well as regions such as the European Union, revise their data sovereignty requirements. They’re tightening the standards to eliminate ambiguity, reduce weaknesses, improve consumer and political confidence, protect businesses, and respond to geopolitical situations, such as economic and military conflicts, terrorism, and cybercrime.

Here's one prediction: Digital sovereignty laws and regulations will increase in number and complexity.

Here’s another: Financial and criminal penalties for failing compliance audits or having data breaches that expose regulated data will be harsh.

Concerns driving the providers of sovereign clouds include protecting customer data from access by admin and support staff as well as maintaining business continuity and compliance with disaster recovery regulations.

Resilience is clearly the name of the game.

Overall, cloud sovereignty is a relatively new concept; organizations are only just starting to understand all the implications it will have on their cloud strategies. Implementing a sovereign cloud means coming to grips with new IT requirements for infrastructure, strategy, governance frameworks, and skills. As the sovereign cloud is a long-term play, organizations are focusing on the domains and regulatory environments that have the most-rigorous regulations while investing in monitoring new legislation and changes to industry rules. Because once regulations tighten, they don’t loosen—it’s a one-way trip.

Choosing a Sovereign Cloud Vendor

When choosing a sovereign cloud, look for the provider that delivers the best overall solution that also helps you meet your digital sovereignty requirements. Ideally, the services available in the sovereign cloud will be the same as those offered in the provider’s public cloud, with the same service level agreements (SLAs) for performance, management, and availability.

One major factor to consider is whether you can go with a single-vendor solution that’s owned and operated by an approved legal entity within the regulated region. Joint ventures and partnerships can lead to finger-pointing over support issues, integration complexities, slower product releases, and, in some cases, fewer available features.

A sovereign cloud provider should offer data sovereignty as a core feature of its cloud, not as a bolt-on package or subset of its public offerings. That will make deployment easier because the sovereign cloud uses the same hardware, software, and services as the public cloud, just with greater access control and other compliance restrictions enabled.

Disaster recovery is critical for sovereign cloud planning and deployments; look for cloud regions within the geography that can be configured with recovery and failover remaining within the compliance area. A sovereign cloud vendor should also have the expertise to help you navigate the complex, ever-changing web of regulations. The vendor and the customer should be able to seamlessly share responsibility for compliance, including accreditations as necessary.

One Step Further: Isolated Regions and National Security Regions

Government networks and highly classified workloads may require customer accreditations and compliance standards that surpass those of internet-connected sovereign cloud regions. In such cases, you may wish to look for isolated regions and national security regions, which can offer additional protection, including the following:

- Government accreditation: Look for national security regions certified to the highest government classifications, including US DISA Impact Level 6.

- Air-gapped data centers: These facilities are built to government specifications that meet or exceed government standards and are not connected to the internet.

- Secure operations: Facilities should be operated and supported by citizens who maintain customer-specific security clearances.

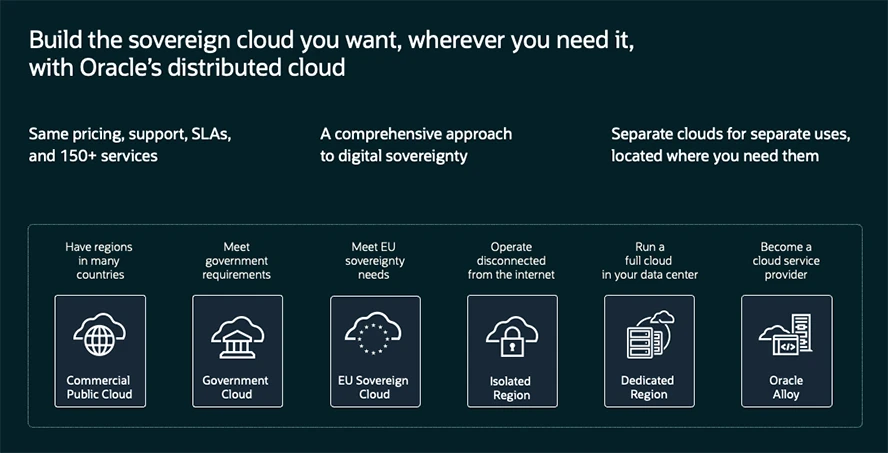

Meet Sovereignty Requirements with Oracle Cloud

Oracle Cloud solutions for sovereignty help customers meet their needs for cloud computing involving data and applications that are sensitive, regulated, or of strategic regional importance, as well as workloads governed by sovereignty and data privacy requirements. Offered in an increasing number of countries and regions around the world, Oracle’s sovereign cloud solutions provide the services and capabilities of Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI) to help customers address their digital sovereignty requirements.

Designed for data residency and security, the Oracle EU Sovereign Cloud architecture shares no infrastructure with Oracle’s commercial regions and has no backbone network connection to Oracle’s other cloud regions. Customer access to Oracle EU Sovereign Cloud is managed separately from access to Oracle Cloud’s commercial regions.

By offering cloud services where data remains within defined geographic and legal boundaries—often with specific operational and governance requirements—providers of sovereign cloud solutions enable governments and highly regulated industries to gain the benefits of the cloud while upholding stringent data residency and security mandates. As the digital landscape continues to evolve and geopolitical considerations remain prominent, sovereign cloud offerings are poised to play an increasingly vital role in enabling digital transformation while helping organizations maintain adherence to relevant rules and laws.

A zero trust architecture provides the visibility and control you need to secure data at its source, enforce access policies based on identity and context—not just network location—and navigate the complexities of data sovereignty.

Sovereign Cloud FAQs

What is data sovereignty?

Governments continually pass laws and regulations about how critical digital information must be stored, where it must be stored, and who is allowed to access it. Data sovereignty encompasses compliance with those laws and regulations by organizations and individuals.

What is an example of a data sovereignty law?

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enacted by the European Union in 2016, has comprehensive requirements for organizations that collect and process the personal information of individuals in the EU.

Who can access information in a sovereign cloud?

Data sovereignty laws may restrict data access to software, services, and users within a specific geography, to companies owned locally, or to those that have specific security clearances or other permissions.

Are sovereign clouds connected to the internet?

For many users, sovereign clouds are connected to the internet via encrypted links with strong access controls. For some government users and highly secure applications, however, the sovereign cloud may be air-gapped and totally disconnected from the internet.

Are cloud backups and disaster recovery scenarios subject to data sovereignty rules?

Yes. Backups and disaster recovery sites must be fully compliant with data sovereignty rules; for cloud sovereignty, that means secondary cloud regions must be within the same geography or regulatory domain.

Why is location important for cloud sovereignty?

Having the ability to choose the geographic regions where they store their data is important for organizations that need to retain control over their data to comply with data sovereignty laws and regulations.